Eight days after entering the world, Khi’Meir Taylor made another debut — this time in what could be a national spotlight.

January 10 was the first day of a $55 million experiment to test whether cash payments can protect children from the toxic stress of poverty.

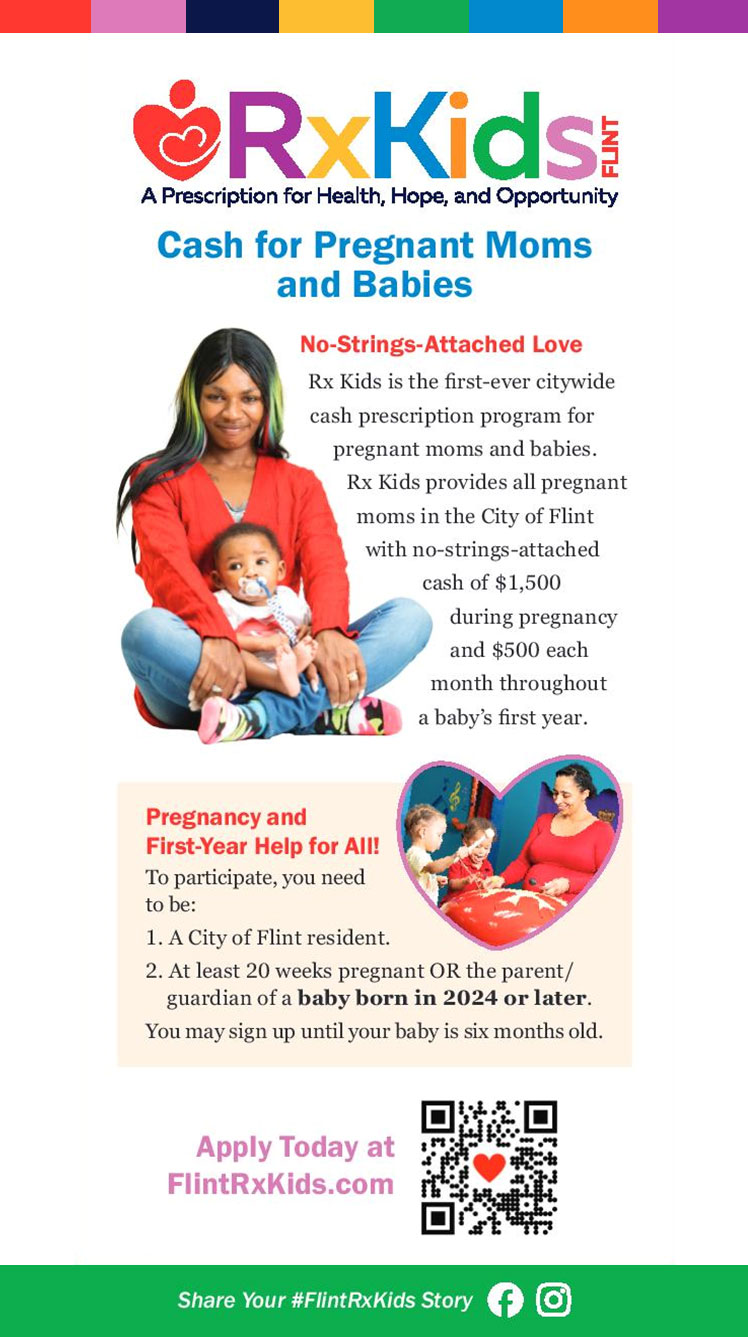

Enrollment opened at 10 a.m. for Rx Kids, an innovative state-funded program that will prescribe no-questions-asked cash allowances to all pregnant mothers and babies in Flint, regardless of their income. Less than an hour after the application process went live online, Dr. Hanna-Attisha held a sleeping Khi’Meir in front of news crews at Hurley Medical Center to celebrate what she called “the incredible, incredible village” supporting the program.

It was Hanna-Attisha whose testing in 2015 revealed that children were exposed to dangerously high levels of lead in the city’s water. In her book about the experience, she argued that the crisis underscored the need to focus on prevention and resilience in a city wracked by the pervasive stresses of poverty. She is now leading the new program.

Flint moms who enroll will receive up to $7,500 to help boost their infant’s footing in the first year of life — a one-time $1,500 payment in mid-pregnancy, followed by $500 per month for the first year of their child’s life.

The program, touted as one of the first of its kind in the nation, aims to stabilize the lives of newborns and their mothers by easing some of the effects of poverty.

While cash assistance programs have launched elsewhere in recent years, Flint’s is the first to serve an entire city and extend it to all families, whatever their income, said H. Luke Shaefer, one of the program’s co-directors. Shaefer is a national expert in poverty and social welfare policy and the director of U-M’s Poverty Solutions, which conducts poverty research.

Rx Kids is also one of only a few programs to focus on the months before birth, he said.

The effort initially began last spring with $15 million in seed money from the Flint-based Charles Stewart Mott Foundation. (Mott is a funder of the Center for Michigan, Bridge Michigan’s parent organization. It had no role in the reporting or editing of this story.)

In July, the state set aside the largest single infusion — $16.5 million. That generated some criticism, including from State Sen. Jim Runestad, R-White Lake, who voted against the state expenditure.

Runestad told Bridge previously that cash handouts without restrictions are “emotional programs” that “create dependence on the government.”

Runestad said the money would be more appropriately distributed through voucher programs that provide families with funds to pay for specific needs, such as auto repairs or respite programs for overwhelmed parents.

Indeed, one 2018 study from Princeton University concluded that cash assistance reduces incentives to work and may harm adults’ earnings over their lifetimes, even if such funds appear to offer a temporary boost.

But other research has repeatedly concluded that “toxic stress” in early childhood disrupts brain development, raising the odds that a child will experience poor physical and mental health later in life and will be more likely to have chronic illnesses, including heart disease, substance abuse and depression.

In 2018, a large review published in the peer-reviewed Journal of Social Policies, examined 165 studies of cash assistance programs around the world and found that, in general, they improved education, health and nutrition, work and a sense of “empowerment” among the recipients.

With the Mott and State funds, the Flint program now has $43 million of its $55 million needed, Dr. Hanna-Attisha said.

As snow threatened outside in one of the state’s poorest cities, dozens of parents and Flint residents gathered with city leaders and Gov. Gretchen Whitmer for what seemed less like a news announcement, and more like a celebration. The event was decorated with teddy bears, pink heart stickers and frosted cookies.

The Kids Rx cash targets the stressors of poverty, but all pregnant women and infants who live in the city, regardless of income, will be eligible. The program also will collect extensive data to measure the money’s impact on participants’ lives and health.

Though critics question the wisdom of giving people money without strings attached, U-M’s Shaefer argued that programs like these are more efficient than cumbersome traditional welfare programs that require expensive oversight.

“If you are really a believer in small government, then this is the program for you,” he said after the event, as city leaders and new parents jockeyed around each other for selfies and group shots.

“So families can spend on whatever they want, and the evidence is clear that they use it incredibly well.”

With Khi’Meir in her arms, his mother, Tateyanna Taylor, 24, said she will spend the money first on eliminating overdue rent bills. She was fired from her job at a Flint factory last year when she passed out at work during her pregnancy, she said. “I need to catch up.”

Teagan Medlin, 25, a former Dollar Store employee, said she’ll spend the money on getting her driver’s license and a car – something that will be critical now that she’s welcomed her third child, Audrina, who was born Jan. 3.

“I’ll need to get my kids where they need to go, to their appointments,” Medlin said, recalling having to rely on others for rides to medical appointments for her second child, a daughter, Delilah, who was born 10 weeks premature.

Medlin also plans to train as a recovery coach, helping people fight substance abuse. “I’m nervous and excited,” she said, adding “I have a community behind me.”

Alana Turner, 28, who is expecting a daughter in April, said any money that isn’t spent on things like diapers, rent payments and other necessities will be set aside for savings for her children.

“As a mother, you have that mindset that any additional income (from the program) is going to be poured into your child,” Turner, a property manager for a rental company, said. “You’re going to want to provide enrichment in any way you can.”

The goal is to address social determinants of health — “the things that are stopping people from getting healthy,” said Jim Ananich, a former legislator who is now the CEO of the Greater Flint Health Coalition.

The cash will allow “families, mothers and children and fathers and family members to thrive and not just barely survive,” he said.

After the event, Ananich stressed that he believes participants will spend the money well.

“Whether you’re a parent with a million dollars in the bank, or barely enough to make ends meet, you care about your kids,” Ananich told Bridge Michigan. “That instinct to be a good parent is in all of us.”